FUSION

Intercultural Projects Berlin e.V.

A Long Journey Through Time and Space

The non-profit association FUSION – Intercultural Projects Berlin e.V. was founded in 1996. At that time, the term “intercultural” was still relatively uncommon; people more often spoke of “multiculturalism” when referring to the ethnic and cultural diversity of society resulting from migration. This implied that many ethnic groups lived side by side in neatly separated and identifiable communities, each shaped by its own cultural heritage. Ideally, such coexistence was expected to be peaceful and harmonious, in keeping with the principles of a humanist, democratic, and pluralistic society. In reality, however, this was far from the case. The 1990s in Germany were marked by violent racist attacks on migrants, their families, and institutions. Many people in the newly reunified country were deeply shaken by these xenophobic outbreaks of violence. Yet symbolic responses such as candlelight vigils were a faint answer to the burning of asylum homes and the many victims of hate-driven aggression. It was against this backdrop that FUSION – Intercultural Projects Berlin e.V. was founded by people from different parts of the world who had all made Berlin their home. They shared a conviction: that dialogue between ethnic and cultural groups needed to be strengthened through cooperation and the creation of creative synergies. Their aim was to develop more powerful symbolic practices against racism, hatred, and violence—anchoring them so firmly in everyday culture that they could serve as a kind of cultural immunization against racism, while also improving conditions for the social integration and inclusion of marginalized groups. At the heart of FUSION’s vision lay the understanding of art as a universal language—capable of transcending cultural boundaries and merging them into new forms of expression. Creativity was seen as the driving force of transformation: a way to dynamize, expand, and reimagine culture into one of respect and acceptance, where intercultural dialogue and communication between different groups could become part of everyday life. These were, in broad strokes, the ideas that more than 25 years ago led to the founding of FUSION – Intercultural Projects Berlin e.V. At that time, Berlin already had the Love Parade and Christopher Street Day—large urban festivals that gave visibility to certain social groups while leaving a lasting mark on the city’s culture. Yet there was no equally strong form of expression representing the presence of migrants. Such a form had to be created.

Carnivalization of Culture

The guiding ideas behind FUSION drew on a long historical tradition: a story shaped by deportation, slavery, colonialism, emancipation, migration, cultural syncretism, self-determination, and resilience in the face of racism, exploitation, and marginalization.

The association’s founders, Marta Galvis de Janzer und Wolfgang Janzer, encountered the Notting Hill Carnival in London in the early 1990s.

Over several years, they worked closely with leading figures of this immense cultural phenomenon—brought to London in the 1960s by Caribbean immigrants, and developed despite the resistance of mainstream British society.

From modest beginnings in the 1960s—when immigrants from Trinidad introduced elements of their homeland’s carnival to the streets of Notting Hill—the event grew into the largest annual festival in the British capital.

By the 1990s, it was attracting over two million people from around the globe.

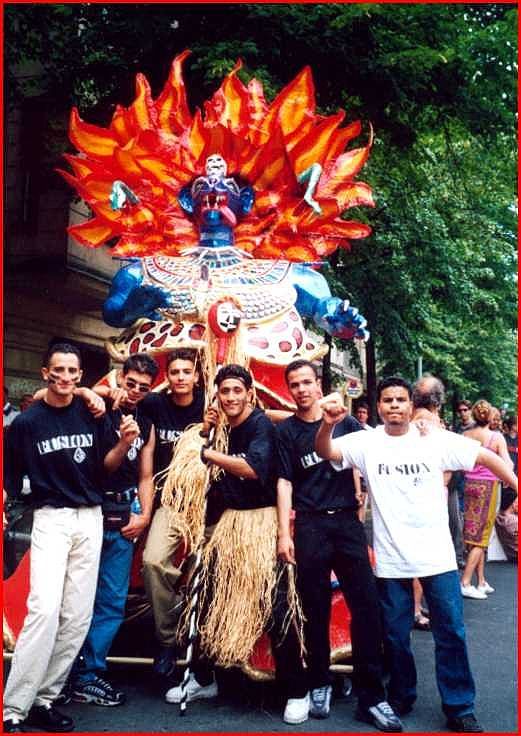

In Notting Hill, all forms of art—music, dance, theater, sculpture, painting—merged into a collective celebration staged in the streets of London.

Organized and produced by immigrants, the carnival nurtured a grassroots cultural network: carnival groups, workshops (often linked to youth and community centers), steel bands, and soca, reggae, and hip-hop sound systems.

This “culture from below” generated a creative energy that surpassed anything produced by Europe’s traditional museum culture.

As a festival of imagination and creativity, the carnival gave immigrants visibility and a voice that could not be ignored.

It became a powerful instrument of self-integration into British society and permanently reshaped the contours of British culture.

Inspired by these experiences, the idea of a Berlin carnival emerged in 1994.

Originally envisioned as the NewKölln Carnival, it was later renamed the Carnival of Cultures by the Werkstatt der Kulturen, a young institution that took over its organization.

The proposal received mixed reactions. Some expressed skepticism, while others—such as the UFA Fabrik and YAAM Club, both long familiar with global culture—responded with immediate support.

Many artists from around the world living in Berlin also embraced the idea and contributed to its realization.

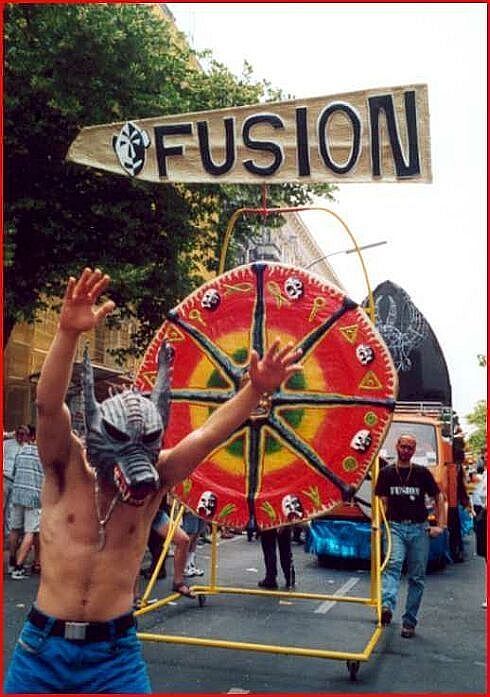

The first Carnival of Cultures took place in 1996, with a parade leading from Hermannplatz in Neukölln to Mariannenplatz in Kreuzberg.

It attracted an audience of 50,000 people.

What some had dismissed beforehand as a “crazy idea” quickly proved itself to be a powerful new cultural expression.

That same year, FUSION – Intercultural Projects Berlin e.V. was established.

The founders recognized that this new, large-scale form of popular expression could not realize its full potential if organized solely by state institutions in a bureaucratic manner.

From the outset, it required strong democratic impulses: the active participation of the very groups that created the masks, costumes, music, and choreographies that came to life on the streets.

The name FUSION was programmatic, expressing the idea of blending diverse cultural elements through carnival culture.

By contrast, the name Carnival of Cultures suggested a folkloristic showcase of cultures existing side by side—a kind of “ethnic display,” well-intentioned but nonetheless paternalistic.

For some of the carnival’s more engaged protagonists, this meant that the official version missed the essence of the idea.

Their answer was simple: to do it themselves.

Thus began the story of FUSION e.V.—driven by the belief in bringing carnivalesque aesthetics into society, cultivating imagination, creativity, joy, collective creation, resilience, autonomy, and the pursuit of emancipation.

The goal was to strengthen mutual responsibility, improve coexistence, and make the future something to be faced with curiosity, joy, and courage rather than fear.

The history of FUSION e.V., like any good story, is one of successes, setbacks, and perseverance.

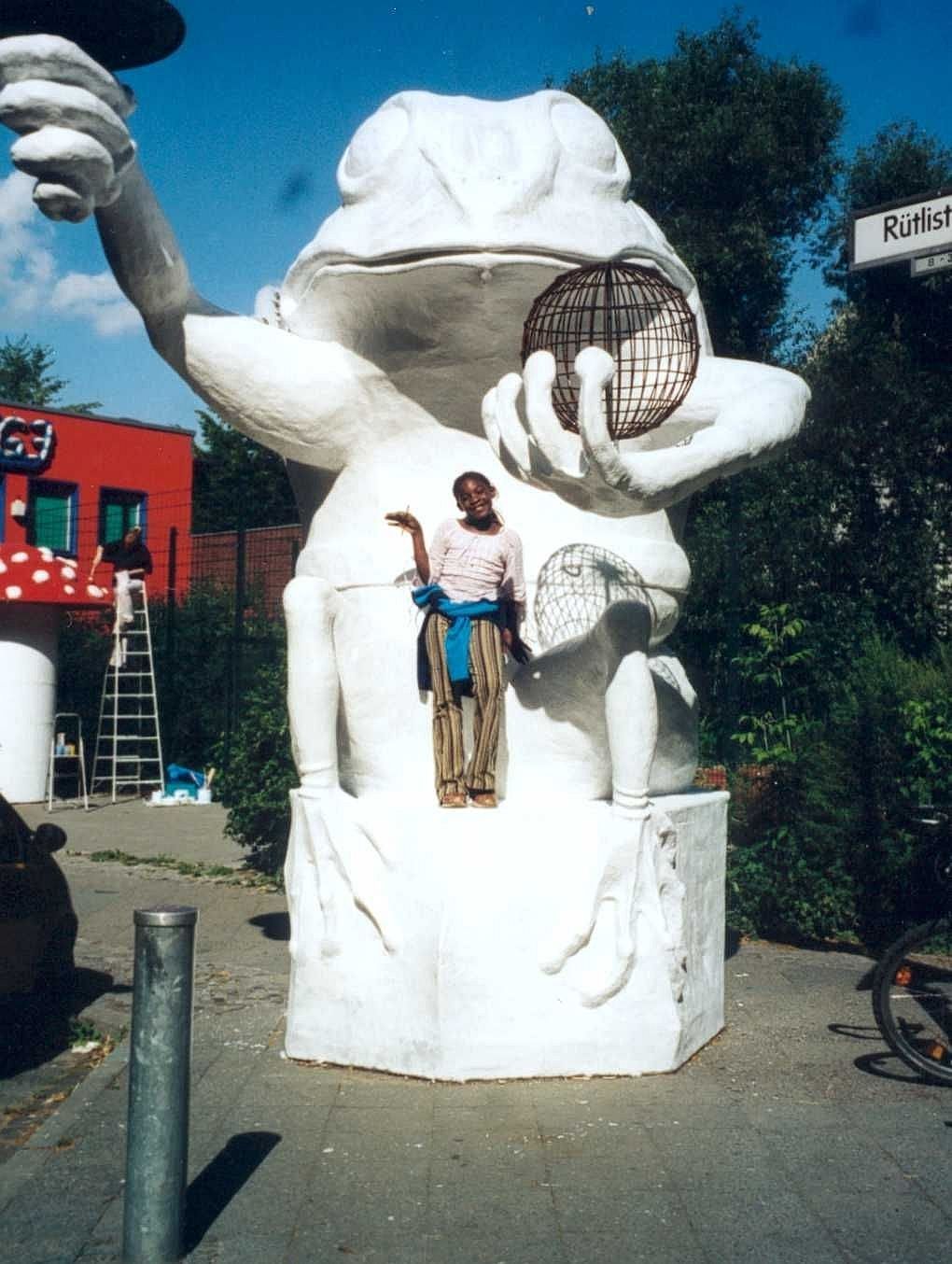

From its wild early years in Kreuzberg in 1999, the association’s work expanded to Neukölln and Marzahn, and later—beginning in 2013—to Brandenburg: first to Strausberg, and in 2016, most recently, to Grünheide.

There, FUSION built the ZEBRA KAGEL cultural space, even before Elon Musk established his Gigafactory in the same area.

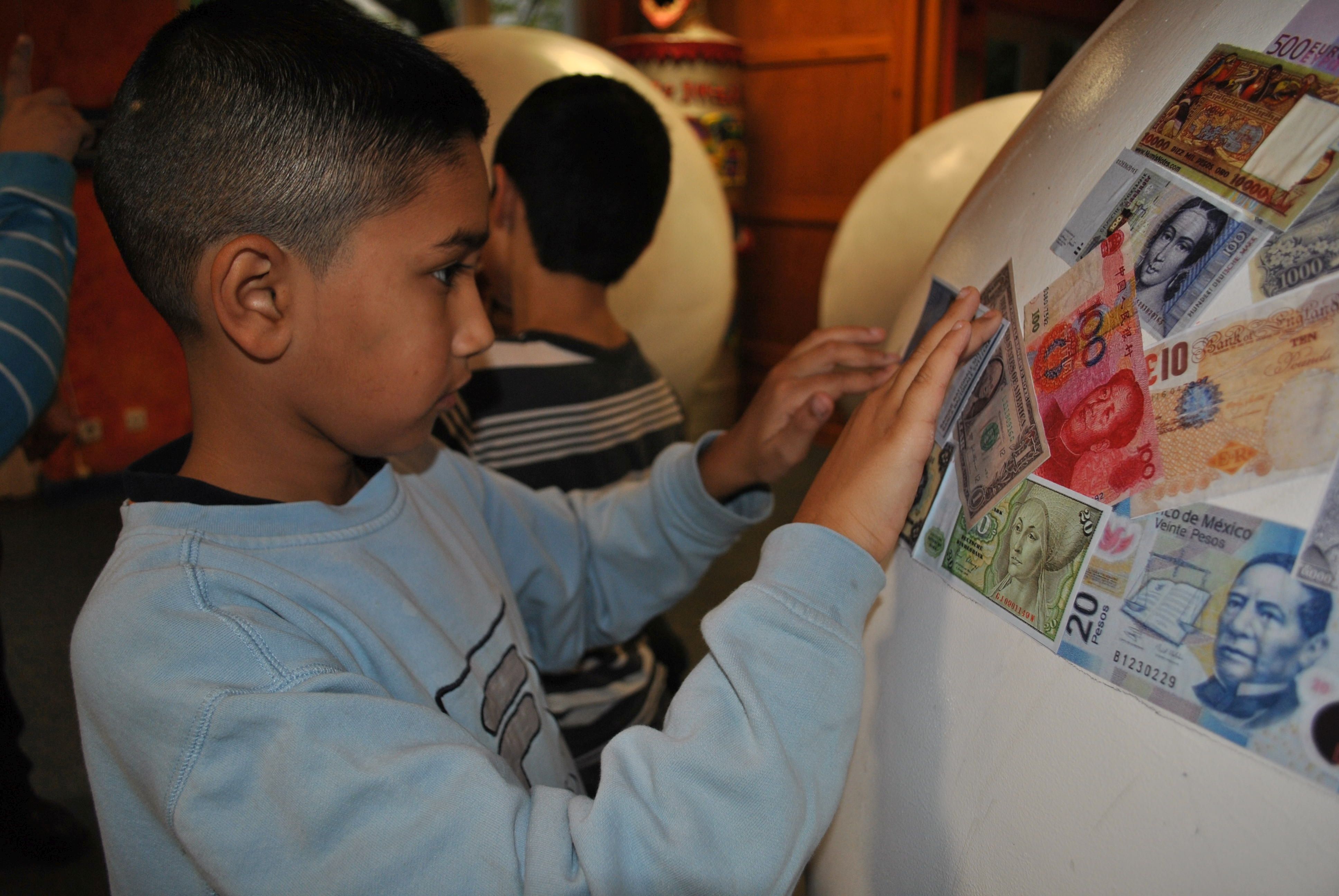

Over time, certain aspects came increasingly to the fore—most notably the fostering of integration through empowerment, education, and a strengthened sense of responsibility among young people; the development of spatial strategies and concrete measures for shaping life in so-called “social hotspots”; and efforts to build neighborhood networks and vibrant community communication.

We understand the biography of the association as the unfolding of an idea within the space-time dynamics of social contradictions. The journey is far from over.

The work of FUSION – Intercultural Projects Berlin e.V. can be explored on this website through numerous texts and visually in photo galleries on a wide range of themes.

Our current home, ZEBRA KAGEL, has its own dedicated website.

Migration Society

Movements of people across significant borders have occurred at all times in history and in almost every place. Migration is a universal practice, a fundamental form of human action.

However, both the nature and scale of migratory movements—as well as the systems that produce borders, and thus the borders themselves—have changed profoundly over time.

Migration has always been an important driving force of social transformation and modernization.

From this perspective, migrants can be seen as actors who bring new knowledge, experiences, languages, and perspectives into diverse social contexts, thereby helping to shape them.

Paul Mecheril, 2012